Islamic art is a modern concept created by art historians in the 19th century to facilitate categorization and study of the material first produced under the Islamic peoples that emerged from Arabia in the seventh century.

Islamic art is not art of a specific religion, time, place, or of a single medium . Instead it spans some 1400 years, covers many lands and populations, and includes a range of artistic fields including architecture, calligraphy , painting, glass, ceramics , and textiles, among others. Early development of Islamic art was influenced by Roman art, Early Christian art (particularly Byzantine art), and Sassanian art, with later influences from Central Asian nomadic traditions. Chinese art had a formative influence on Islamic painting, pottery, and textiles.

Themes of Islamic Art

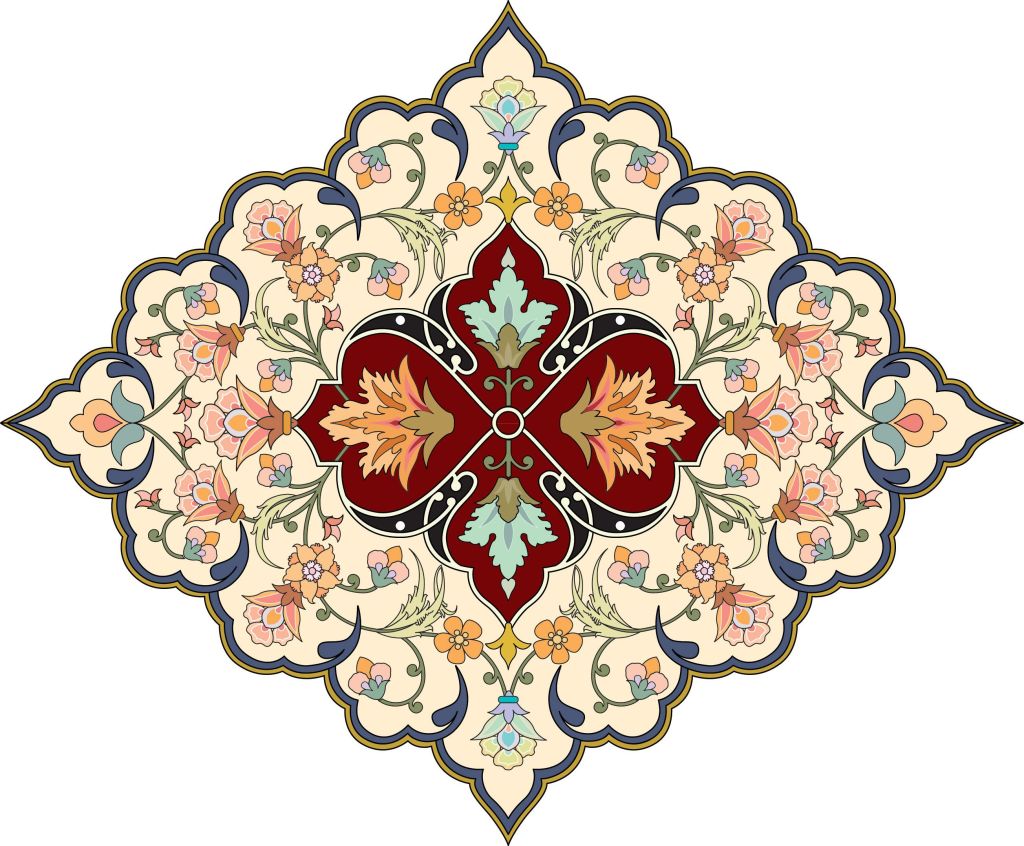

There are repeating elements in Islamic art, such as the use of stylized , geometrical floral or vegetal designs in a repetition known as the arabesque . The arabesque in Islamic art is often used to symbolize the transcendent, indivisible and infinite nature of God. Some scholars believe that mistakes in repetitions may be intentionally introduced as a show of humility by artists who believe only God can produce perfection.

Typically, though not entirely, Islamic art has focused on the depiction of patterns and Arabic calligraphy, rather than human or animal figures, because it is believed by many Muslims that the depiction of the human form is idolatry and thereby a sin against God that is forbidden in the Qur’an.

However, representations of Islamic religious figures are found in some manuscripts from Persian cultures, including Ottoman Turkey and Mughal India. These pictures were only meant to illustrate the story.

Calligraphy

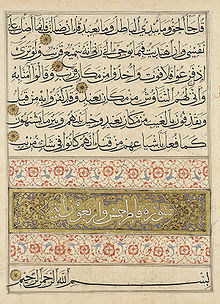

Calligraphy is a very important art form in the Islamic world. The Qur’an, written in elegant scripts, represents Allah’s divine word. Use of Islamic calligraphy in architecture extended significantly outside of Islamic territories; one notable example is the use of Chinese calligraphy of Arabic verses from the Qur’an in the Great Mosque of Xi’an. Likewise, poetry can be found on everything from ceramic bowls to the walls of houses.

Islamic calligraphy developed from two major styles: Kufic and Naskh. There are several variations of each, as well as regionally specific styles. . East Persian pottery from the 9th to 11th centuries decorated only with highly stylized inscriptions, called “epigraph ware”. Large inscriptions made from tiles, sometimes with the letters raised in relief, or the background cut away, are found on the interiors and exteriors of many important buildings. Coins were another support for calligraphy. Beginning in 692, the Islamic caliphate reformed the coinage of the Near East by replacing Byzantine Christian imagery with Islamic phrases inscribed in Arabic.

Bowl with Kufic Calligraphy, 10th century

Muhaqqaq, Naksh script in a 14th-century

For centuries, the art of writing has fulfilled a central iconographic function in Islamic art. Although the academic tradition of Islamic calligraphy began in Baghdad, the center of the Islamic empire during much of its early history, it eventually spread as far as India and Spain. Arabic or Persian calligraphy has also been incorporated into today’s modern art.

Geometric patterns

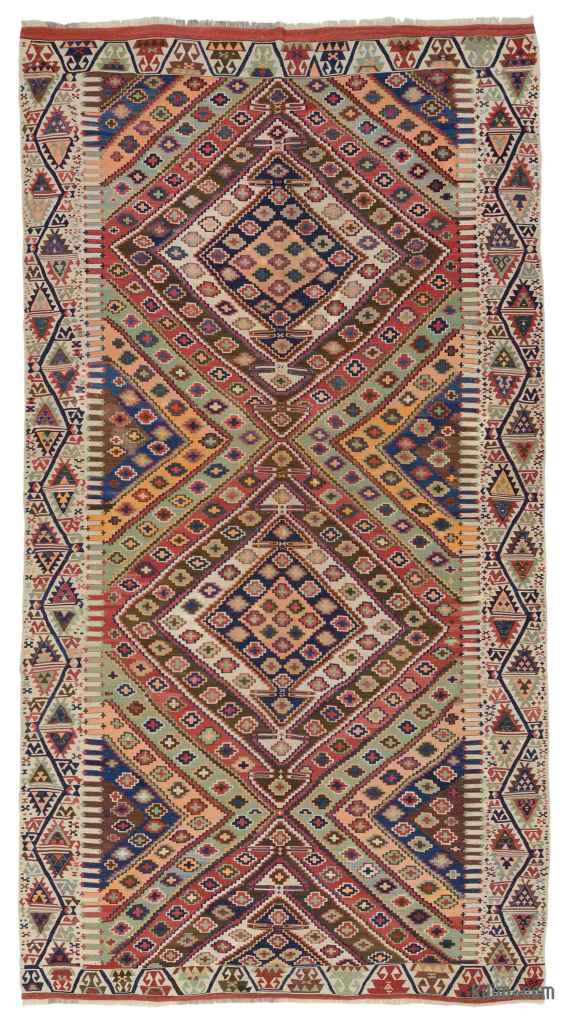

Islamic decoration, which tends to avoid using figurative images, makes frequent use of geometric patterns which have developed over the centuries. The geometric designs are often built on combinations of repeated squares and circles, which may be overlapped and interlaced, as can arabesques (with which they are often combined), to form intricate and complex patterns. A recurring motif is the 8-pointed star, often seen in Islamic tile work; it is made of two squares, one rotated 45 degrees with respect to the other. The fourth basic shape is the polygon, including pentagons and octagons. All of these can be combined and reworked to form complicated patterns with a variety of symmetries including reflections and rotations.

These patterns occur in a variety of forms in Islamic art and architecture including kilim carpets, Persian girih and Moroccan zellige tilework, muqarnas decorative vaulting, jali pierced stone screens, ceramics, le ather, stained glass, woodwork, and metalwork.

Kalim from Turkey

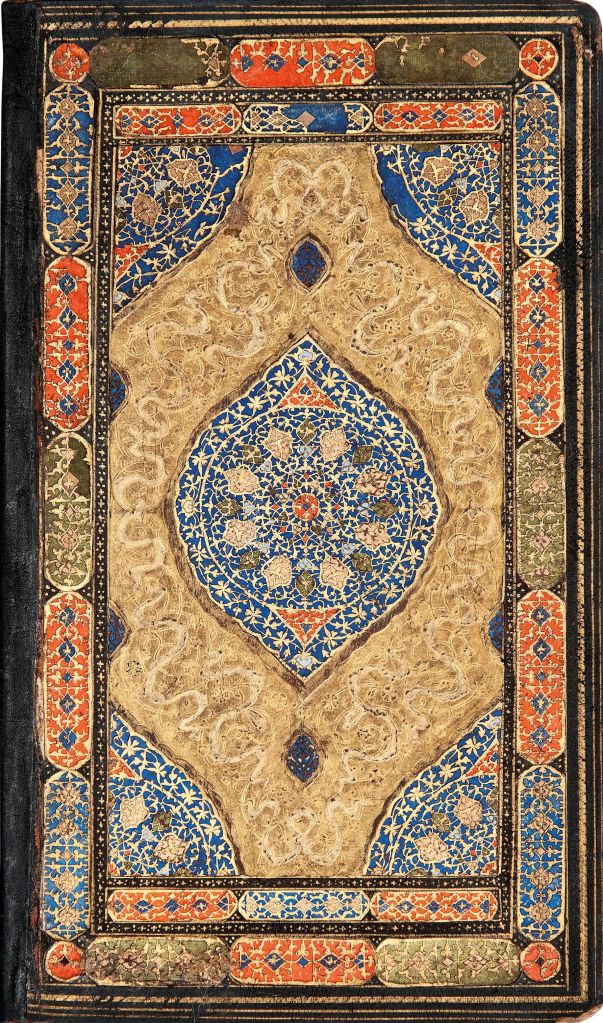

Leather prayer book cover, Persia, 16th century

Girih at Shah-i-Zinda in Samarkand, Uzbekistan

Purpose

Islamic patterns are created to lead the viewer to an understanding of the underlying reality, rather than being mere decoration, as writers interested only in pattern sometimes imply. In Islamic culture, the patterns are believed to be the bridge to the spiritual realm, the instrument to purify the mind and the soul. It is said that their the aim was to transfigure, turning mosques “into lightness and pattern”, while the decorated pages of a Qur’an can become windows onto the infinite.

Floral Patterns in Islamic Decoration

Islamic artists habitually employed flowers and trees as decorative motifs for the embellishment of cloth, objects, personal items and buildings. Their designs were inspired by international as well as local techniques. For instance, Mughal architectural decoration was inspired by European botanical artists, as well as by traditional Persian and Indian flora.

A highly ornate as well as intricate art form, floral designs were often used as the basis for “infinite pattern” type decoration, using arabesques and covering an entire surface. The infinite rhythms conveyed by the repetition of curved lines, produces a relaxing, calming effect, which can be modified and enhanced by variations of line, color and texture. Sometimes the ornate would be emphasized, and floral designs would be applied to tablets or panels of white marble, in the form of rows of plants finely carved in low relief, along with multi-colored inlays of precious stones

Ornamentation of Surfaces Dissolves Matter

One of the most fundamental principles of the Islamic style deriving from the same basic idea is the dissolution of matter. The idea of transformation, therefore, is of utmost importance. The ornamentation of surfaces of any kind in any medium with the infinite pattern serves the same purpose – to disguise and ‘dissolve’ the matter, whether it be monumental architecture or a small gold box. The result is a world which is not a reflection of the actual object, but that of the superimposed element that serves to transcend the momentary and limited individual appearance of a work of art drawing it into the greater and solely valid realm of infinite and continuous being.